A prolonged heatwave

The drought we are currently experiencing brings us face to face with the reality of climate change. According to Météo France, with global warming, droughts will become five to ten days longer by 2050.

However, May and June were well watered. “But at this time of year, rainwater doesn’t penetrate very deeply. It moistens the soil and benefits growing vegetation,” explains Violaine Bault, hydrogeologist at the French Geological Survey (BRGM). The groundwater tables were recharged this winter, but began emptying earlier than usual, as early as February, due to the lack of precipitation.

The situation of France’s terrestrial, aquatic and marine ecosystems continues to give cause for concern.

Drought: “Everyone knew about it, but no one anticipated,” exclaims Jean-Malo Cornée, President of the Établissement Public Territorial de Bassin Rance, Frémur et Baie de Beaussais (EPTB), and hopes that “everyone, elected representatives and consumers alike, will assume their responsibilities”. From Monday July 18, 2022, his department will be under a reinforced drought alert.

Cold Sweats

The causes of prolonged periods of drought in France and the rest of the world have long been known.

One of the main reasons for this is land artificialisation. Human development has intensified soil sealing, creating new “water barriers”: asphalt roads, urbanization, deforestation and compaction of agricultural soils.

There are also other causes, such as water leaks, both in supply networks and in private homes. Laurent Roy, Managing Director of the Rhône Méditerranée Corsewater agency since 2015, alarms us: ” Leaks, losses that are sometimes considerable: in some networks, more than half the water is lost before it reaches the tap”.

Water misuse is another example of the problem of water management. From poorly managed watering systems to the waste of water in daily use, we need to reconsider our entire philosophy of using natural resources. France reuses just 0.5% of its wastewater, compared with 10% in Spain, 60% in Malta and 90% in Cyprus. These are sobering figures.

Small bathtub problem

Save water, switch to a dry toilet!

Drinking water accounts for 25% of overall water consumption in France. This corresponds to around 6 billion cubic meters per year. This figure is stable overall, as the increase in population is offset by a reduction in individual consumption.

The average French person consumes 150 liters of water a day. Of these 150 liters of drinking water, 20% are used to flush our toilets (30 liters), while only 7% are used for food.

Do we have to say it? Consuming water – and drinking it for our toilets – is an aberration that borders on scandal.

Water management in France, “Ça ruisselle!

France organizes its water management through agencies whose scope of action corresponds to the course of major rivers. Financed by a levy on the water bill, they support all kinds of projects to reduce wastage, restore natural ecosystems, restrict abstraction to protect water tables and rivers…

In accordance with European directives, the agencies implement the “polluter pays” and “user pays” principles, in a way that can be summed up by the phrase “water pays for water”. These powers are then transferred to the regions, departments and localities. So it’s up to all levels of the administration to work towards sobriety.

And if it’s estimated that an average of 33.5 billion cubic metres of water are abstracted from our country every year, and that drinking water accounts for around 6 billion cubic metres, our personal consumption may seem like a drop in the ocean. It’s an illusion: whether it’s the water-hungry textile industry, or the nuclear power plants that use water to cool their reactors, we are the consumers at the end of the production chain. A paradigm shift is needed, which must be implemented at every link in the chain.

A tank of solutions

A few ways to save water

Solutions exist at every level. And we need to act at all levels.

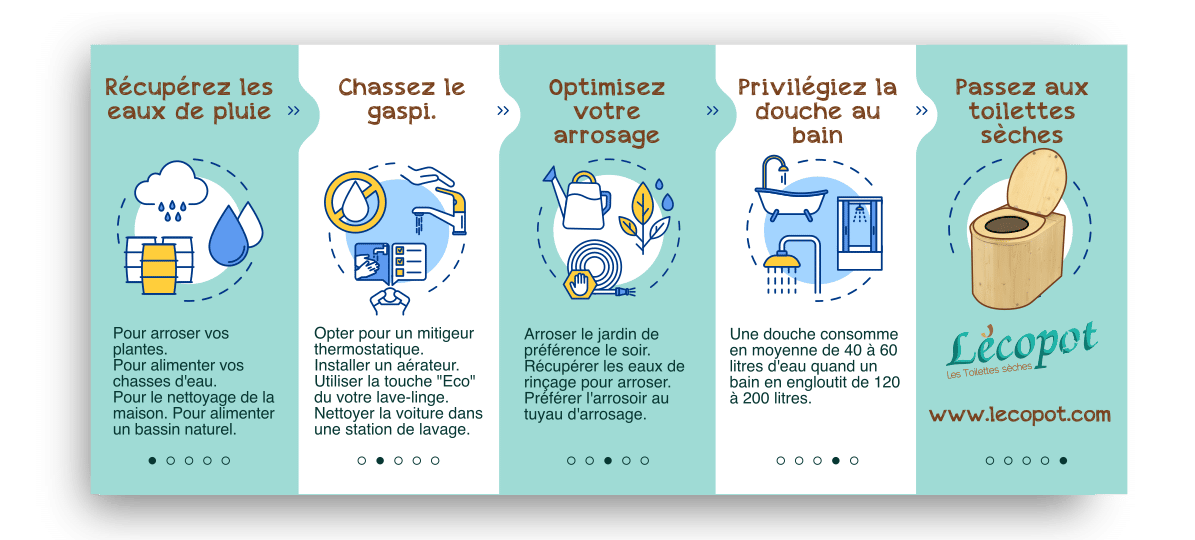

For the home, here’s a short list of actions that can make a difference.

1. Eliminate water leaks.

2. Choose showers over baths.

3. Choose a thermostatic mixing valve and insulate your water heater.

4. Use the rinse water to water your plants.

5. Install a mousseur or aerator on your faucets and showerheads.

6. Install a dual-flush toilet.

7. Use the “eco” button on your washing machine or dishwasher and fill it completely.

8. Clean your car at a car wash.

9. Collect and store rainwater.

10. Water your garden preferably in the evening.

As far as local authorities are concerned, “there’s a whole range of solutions”, assures Laurent Roy. À Starting with the fight against waste, which concerns everyone. Leaks, losses sometimes considerable. Supply systems need to be modernized, with tools to control network leaks. Another approach is to increase water resources, firstly by recovering rainwater before it runs off into the streets and becomes loaded with hydrocarbons and other toxic products.

Recreate surfaces that allow rainwater to infiltrate. It’s a question of forcing water into the ground,” explains Violaine Bault of BRGM. You can do this in the city as well as in the country. Hedges, grassed strips, ploughing at right angles to the slope and winter crops keep the water in”. Double benefit: these zones limit flooding and recharge aquifers.

Another technique to be developed is groundwater recharge. Retention basins can be dug to temper the river’s flooding. Artificially recharging groundwater has other advantages. This dilutes pollution in the water table, or acts as a barrier to seawater.

Improve irrigation. “The water supplied must be used to the maximum by the plant,” explains Crystèle Léauthaud, agrohydrologist at the Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement (CIRAD). The aim is to replace surface irrigation (runoff on plots of land) with via canals) by other techniques, such as drip irrigation or sprinkling. But “beware of the rebound effect”, warns Crystèle Léauthaud. “We don’t want the water saved to be used to irrigate a new plot.

A number of factors, such as rainfall intensity and quantity, vegetation cover, biological activity and human development, can influence the soil’s capacity to absorb water. Vegetation cover helps to reduce the intensity of rainfall by creating a barrier to runoff and maintaining good soil structure.

Measures are currently being taken to enable stormwater to return to its natural course. An increasing number of cities are implementing a policy of infiltrating rainwater into plots of land (as in Rennes and Paris). Farmers are also changing their practices to avoid leaving the soil bare (winter crops), to loosen soil compaction and to block runoff with hedges and grass strips.

The forgotten dry toilet

Join our FB group: toilettes sèches & fières de l’être!

yet central to the approach to ecological

ecological sanitation

as a prerequisite for an

circular economy

waste natural resources, the dry toilet is not mentioned in the recommendations issued by the government to combat water shortages.

By no longer disposing of our dejecta in waterways, we reduce nitrogen and phosphate pollution in our rivers “and virtually eliminate bacterial pollution” (D. Marchand, DRASS sanitary engineer). On the other hand, with wet toilets, some of this pollution remains, even after treatment by non-collective sanitation systems or collective wastewater treatment plants.

The dry toilet is two benefits in one.

Firstly, “drinking” water savings are considerable with the use of biolitter dry toilets. If a person consumes 30 liters of water a day when flushing the toilet, it’s easy to calculate the daily cost of drinking water for a population of 67,813,396 in France today. All this preserved water will save energy in transport, pre-treatment and post-treatment, not to mention the costs of maintaining the associated infrastructure.

The second major benefit is soil enrichment through the production of quality compost. For, as mentioned above, plant cover helps to reduce the intensity of rainfall, creating a barrier to runoff, and maintains good soil structure.

Feeding the soil with rich compost allows us to fertilize the soil in which we will have planted trees and bushes that will retain water run-off and help maintain a humid atmosphere.

Finally, from a more productivist point of view, let’s imagine the benefits of recovering materials. The production of biogas, composed of 60% methane, can be extracted from human excrement around the world through the decomposition of the material by bacteria, and would be worth up to $9.5 billion in natural gas equivalent, according to a study by the Canadian-based Institute for Water, Environment and Health.

So why do dry toilets seem condemned to remain confined to the private sphere of our homes, a few forward-thinking public events or private companies keen to make a difference? Why haven’t the state and its institutions yet grasped this obvious solution?

Regulations governing the use of human and/or animal excrement can hinder production and the export or import of agricultural products produced in this way. But feedback shows that revising legislation is necessary, but not sufficient; it’s important to involve the “institutional landscape” and all stakeholders, via parallel processes at all levels of governance, from national to local .

Despite the general promotion of a

circular economy

and the support of the World Health Organization (WHO), socio-psychological, cultural and sometimes regulatory obstacles still need to be overcome, because in wealthy countries and among the ruling classes, the subject of excrement still seems taboo or embarrassing, and elsewhere the subject is rarely fully integrated into public and social policy and discourse. Joseph Jenkins recognizes that there is still a great deal of taboo associated with the processing of fecal matter. “As long as we see excrement as waste, it’s a psychological barrier that prevents us from seeing it as a recyclable and reusable material.”

Yet some countries, like Quebec, are leading the way. By 2021, Quebec City will have its own biomethanization plant, transforming 86,000 tonnes of food waste and 96,000 tonnes of municipal sludge into 6.6 million cubic metres of biomethane.

Today, we’re still in a consumer culture. The term consumption immediately brings to mind our purchases, the use of our cars and machines, the cost of transporting our food products, our consumption of electricity, water and wood – in short, the burden we place on our environment. But the term “consumption” covers a more general idea. It’s to consider ourselves, humans, as beings who weigh on natural resources without collaborating in any way. So the only solution we can see to the problem is to reduce the amount we consume.

Another approach is to consider that we are part of the natural cycle of this environment. In this way, our actions, our productions and what we use are all part of a global cycle that is inseparable from who we are. This idea leads us to consider all our actions in terms of what they take from the environment and what they bring back to it. The dry toilet is a perfect example of this sustainable and rewarding approach. In fact, what we consume, we transform and return to the environment to nourish it in return.

“After a long period of trial and error, science now knows that the most fertile and effective fertilizer is human fertilizer.

Victor Hugo (1802-1885), “L’intestin de Léviathan – La Terre appauvrie par la Mer”, Les Misérables, Livre II,5e partie, p. 686-687.

Sources :

https://www.gouvernement.fr/risques/secheresse

https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/secheresse

https://www.lesagencesdeleau.fr/les-agences-de-leau/les-six-agences-de-leau-francaises/

http://www.slate.fr/story/209672/pluies-mai-mieux-affronter-secheresse-ete-nappes-phreatiques

https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/gestion-leau-en-france

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toilettes_s%C3%A8ches

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assainissement_%C3%A9cologique

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mati%C3%A8re_f%C3%A9cale_humaine#Toilettes_s.C3.A8ches

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utilisation_des_excreta

https://www.quebecscience.qc.ca/environnement/la-deuxieme-vie-de-nos-excrements/